The Flow of Spoon Carving

What is 'Flow'?

At its most basic, flow is when we are in a state of optimal

performance, completely immersed in the activity we are doing. Studies have found there are six

factors that identify a ‘flow’ state:

1. Intense and focused concentration on the present

moment

2. Merging of action and awareness

3. A loss of reflective self-consciousness

4. A sense of personal control or agency over the

situation or activity

5. A distortion of temporal experience

6. Experience of the activity as intrinsically rewarding,

also referred to as autotelic experience

The psychological term 'flow' was introduced by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in

the 1970s, but the subject has scientific roots going back to the early 1900s

with research into

how the brain alters consciousness to improve performance.

More recently, technological advances have allowed us to scientifically

measure what is going on in our brains whist we are in a state of flow.

Neurobiological studies have found that a state of flow comes from a radical

change in normal brain function.

In flow, as attention heightens, the slower and

energy-expensive extrinsic system (conscious processing) is swapped out for the

far faster and more efficient processing of the subconscious, intrinsic system.

(source).

Another study, this time using fMRI scans of jazz musicians in a flow

state, found that the parts of the brain where a lot of our self-checking comes

from shuts down, giving freedom to “spontaneous

creativity”.

Neuroscientists

have also found that endorphin, norepinephrine, dopamine, anandamide, and

serotonin are released during flow. These are pleasure-inducing,

performance-enhancing neurochemicals, which help improve reaction times,

attention, pattern recognition and lateral thinking.

Being in a ‘flow’

state therefore not only improves performance, but it also has a lasting effect

on our happiness. Activities that induce flow are positively correlated with

happiness and transcendent experience.[1]

The enjoyment that flow gives us is dependant

on the quality of the flow state and can have a lasting impact on how

satisfied we are with life.[2]

How to achieve flow

1. Clear goals

You need to know what it is you hope to achieve in order to help direct and concentrate your focus on the task.2. Immediate feedback

Knowing whether or not you are achieving your goals helps to maintain focus. Seeing the immediate influence of your actions keeps you focused on the present, helping toprevent the mind from wandering.

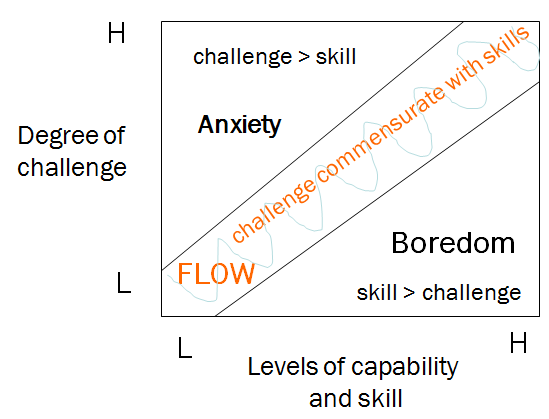

3. Balance between difficulty and ability

|

| Discovery in Action |

4. Focused attention

The flow state requires concentration on the task at hand. Not only does the task need to be completed in a context that allows for the removal of distractions, but a high level of risk helps to hone one's focus.

Flow and spoon carving

As flow has a highly positive impact on our wellbeing, it is an important state of consciousness to try and achieve. Spoon carving is an excellent way to achieve flow, and spoon carvers looking to improve their work can help themselves by creating conditions that are conducive to entering a state of flow. Here's how:

1 Setting clear goals

A tried and tested way of setting clear goals is to use the SMART method. Goals should be:

Specific

Measurable

Attainable

Realistic and

Time based.

Spoon carving naturally gives immediate feedback. The impact of each cut is apparent as soon as it is made. New shapes and grain textures emerge after every pass of the knife.

As such the spoon will take shape and evolve the whole time you work on it. There can be some delayed feedback from greenwood as the final shape of a spoon can twist and 'move' as the wood dries, but often the change is subtle.

3 Balance difficulty and skill

One of the great joys of spoon carving is that to create and object that is able to scoop food or other objects is quite easy. Carving the ergonomically and aesthetically perfect spoon is something we can spend a lifetime doing. Our work therefore tends to fall somewhere between those two markers of success.

As the process of creating a spoon is entirely about the removal of material, one will always reach a point where one has to stop for the piece to remain functional. This gives every spoon we start to carve some nice limits to work within. Are we able to balance function and form within the limited amount of material we have to work with? If we haven't found that balance with our latest spoon, can we create it with the next? For myself I am beginning to recognise anxiety creeping in with regards to the thickness of the spoon bowl. Too thick and the spoon will feel clunky in the mouth. Too thin and it lacks durability. Finding the right thickness is different for every spoon due to variations in the wood being used. Some species are stronger than others, bent wood (where the curve of the grain follows the curve of the bowl) can be carved thinner than a spoon carved from a straight grained section of the same tree.

4 Focused attention

It is difficult to carve a spoon and do another activity at the same time. Setting aside time to just carve without distractions makes it easier to achieve flow.

Activities that have a high level of potential risk tend to correlate with entering a state of flow. While good technique means that the risk of injury from carving can be effectively managed, any time such tools are used, the risk of serious injury is present.

Thus the use of sharp edged tools helps concentrate our focus, increasing the likelihood of reaching a state of flow.

What do you do to try and achieve flow in your carving?

[1] Tsaur, Yen, & Hsiao (2013):

Transcendent Experience, Flow, and Happiness for Mountain Climbers

[2] Collins, A. L., Sarkisian, N., &

Winner, E. (2009). Flow and happiness in later life: An

investigation into the role of daily and weekly flow experiences. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(6), 703-719.

investigation into the role of daily and weekly flow experiences. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(6), 703-719.